It was the Summer of 1978. I was a teenager coming out while spending my break working in San Francisco. This is my journey. Being a gay man/boy in the ’70s felt like being part of a revolution, to be in the vanguard of LGBTQ folks fighting to live our lives completely out of the closet. Back then Gay sex was our “fuck you” to the establishment.

The late ’70s was the height of the lesbian separatist movement. Yes, there was a time with some members of the lesbian community worked to create a world that did not include men, particularly straight, white, cisgender men. Gay men started building our own safe communities that included bars, restaurants, and bathhouses with an explosion of new businesses, jobs, and opportunities. It was the beginning of the community-led infrastructure that would serve as a critical foundation after AIDS. There was little to no awareness of issues impacting people of color. I was often an anomaly in a sea of White people. However, it’s not fair to use a 2022 lens on the ‘70s.

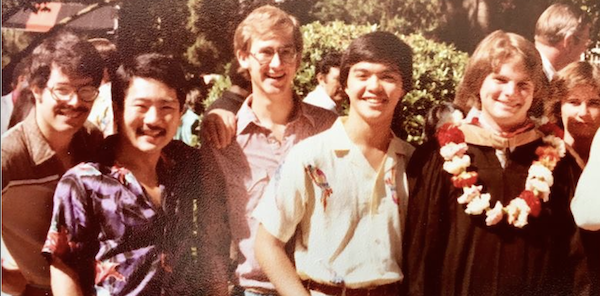

Gay men were divided between those fighting for acceptance by straight society versus those who wanted as much sex as possible. It was the heyday of bathhouses, backrooms, and glory holes. Honestly, it was lots of fun. 1978 was my summer of firsts. Going to my first gay bar, dancing with another man, marching in Pride, and my first real passionate kiss. He was the president of my fraternity, and I was in love.

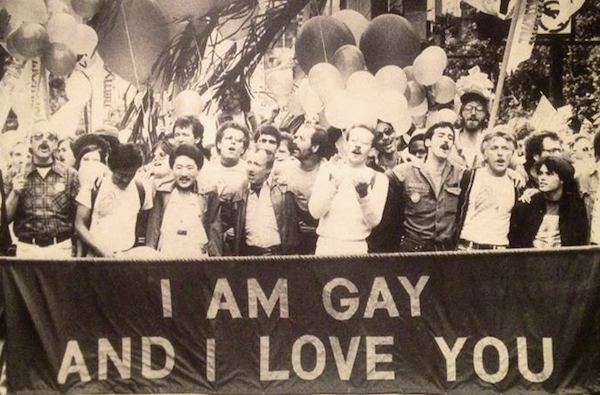

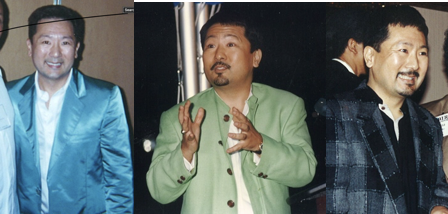

This photo was taken at San Francisco’s Pride Parade. Published on the cover of the San Francisco Chronicle, it was how I came out to my Asian family and friends. As you can imagine, my mother was horrified. 1978 was also the summer I met David Goodstein (publisher of The Advocate), Jim Hormel (philanthropist), and Rob Eichberg (therapist and creator of National Coming Out Day), three men who changed the course of my life. They helped me see that being gay was about more than sex. My life did not have to be lived in the shadows of a closet. I could be the outrageous gay man I wanted to be. That was a revelation, completely contrary to all my Japanese upbringing. They helped me understand the importance of committing my life to something bigger than just me. Being gay was a gift and not the burden I was feeling.

AIDS completely changed the LGBTQ narrative. After my summers of love in San Francisco, I moved to Seattle for dental school. One fateful day, I read an article in the New York Native by Larry Kramer. It turned my life and the lives of people I loved upside down. Our community had to grow up and we had to do it quickly. Hard core lesbian separatists became caregivers for too many gay men. We came together because the world, particularly people in power, did not care about anyone with AIDS. There was no room for our sick. Many White gay men who thought they were being accepted into the larger society were in for a very rude awakening. For the first time they were treated like second class citizens and it made them mad, something very familiar to people of color.

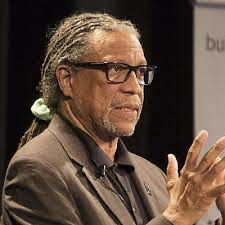

I’m sharing my memories to remind us of who we were and the challenges we’ve overcome, to remember our courage, power, and strength in the face of adversity. In our many and various iterations as people of color, people living with HIV, LGBTQ, women, drug users, and sex workers, we faced what seemed insurmountable and survived; however, there are still too many causalities. As I look back from where I started, I am amazed what this little scared Japanese boy created. Our journey is not over. We still must end the epidemics of HIV, STDs, and Hepatitis, to commit our lives to something bigger than ourselves. And to look back to a life well lived.

Yours in the Struggle,

Paul Kawata

NMAC

The call from the hospital. A stranger telling you to come quickly because your friend is about to pass. When I got the call for Michael, I was in Washington and needed to rush to New York. I remember hopping that shuttle and praying that he would hold on so I could say goodbye. The taxi ride from LaGuardia to Saint Vincent’s was one of the longest in my life. As I rushed down the hall, I saw Michael’s mother and sister sobbing. My heart sank. I thought he was gone. Just then Rona Affoumado came up to me and said “Oh God, you just made it. The family has just decided to pull the plug.” I wasn’t too late. Rona escorted me into Michael’s room. It was all pumps and whistles from the many machines trying to keep him alive. It had that funny smell, the smell of death. Michael had been unconscious for the last 24 hours. The morphine had stopped the pain and allowed him to sleep. As they turned the machines off, there was an eerily silence. I held Michael’s hand and told him how much I loved him. Just then, his eyes opened, and a single tear rolled down his cheek… and then he was gone. The nurse would later tell me that his opening his eyes was probably just a reflex, but to me it was a sign. It was Michael saying goodbye. I close my letters and emails with “Yours in the struggle” to honor his life and the lives of so many that we lost.

The call from the hospital. A stranger telling you to come quickly because your friend is about to pass. When I got the call for Michael, I was in Washington and needed to rush to New York. I remember hopping that shuttle and praying that he would hold on so I could say goodbye. The taxi ride from LaGuardia to Saint Vincent’s was one of the longest in my life. As I rushed down the hall, I saw Michael’s mother and sister sobbing. My heart sank. I thought he was gone. Just then Rona Affoumado came up to me and said “Oh God, you just made it. The family has just decided to pull the plug.” I wasn’t too late. Rona escorted me into Michael’s room. It was all pumps and whistles from the many machines trying to keep him alive. It had that funny smell, the smell of death. Michael had been unconscious for the last 24 hours. The morphine had stopped the pain and allowed him to sleep. As they turned the machines off, there was an eerily silence. I held Michael’s hand and told him how much I loved him. Just then, his eyes opened, and a single tear rolled down his cheek… and then he was gone. The nurse would later tell me that his opening his eyes was probably just a reflex, but to me it was a sign. It was Michael saying goodbye. I close my letters and emails with “Yours in the struggle” to honor his life and the lives of so many that we lost.

Just to be clear, I am not a therapist, but I do have one. I get one hour every other week to talk just about me and my fears. This is a privilege that is not available to most people and that needs to be fixed. I’m transparent about therapy to dispel the stigma and fear surrounding this topic. I grew up in a world where depression was viewed as a sign of weakness. Only rich White people had psychiatrists. I feel pain because I am a person of color living in America. Buck up and get over it. As a result, I spent too many years not addressing the elephant in the room. I’m in pain. The early days of the epidemic had taken their toll. I never took the time to reconcile what happened to me and my friends and to weep for all that was lost. There was a whole generation taken too soon.

Just to be clear, I am not a therapist, but I do have one. I get one hour every other week to talk just about me and my fears. This is a privilege that is not available to most people and that needs to be fixed. I’m transparent about therapy to dispel the stigma and fear surrounding this topic. I grew up in a world where depression was viewed as a sign of weakness. Only rich White people had psychiatrists. I feel pain because I am a person of color living in America. Buck up and get over it. As a result, I spent too many years not addressing the elephant in the room. I’m in pain. The early days of the epidemic had taken their toll. I never took the time to reconcile what happened to me and my friends and to weep for all that was lost. There was a whole generation taken too soon. Here I am, 40 years later, and I can still recall the deaths of too many people. The hospital rooms that had that awful antiseptic smell. The nurses who became my best friends as they made up a bed so I could stay in the hospital rooms of friends. Colleagues who died too quickly so friends could not say good-bye. Friends who lingered too long in pain, fighting for every breath. I was a kid in my 20s when the epidemic started, too young to understand the enormity of what was happening to me and my friends. Too naive to be afraid, I just wanted to help.

Here I am, 40 years later, and I can still recall the deaths of too many people. The hospital rooms that had that awful antiseptic smell. The nurses who became my best friends as they made up a bed so I could stay in the hospital rooms of friends. Colleagues who died too quickly so friends could not say good-bye. Friends who lingered too long in pain, fighting for every breath. I was a kid in my 20s when the epidemic started, too young to understand the enormity of what was happening to me and my friends. Too naive to be afraid, I just wanted to help. I am wounded. It is what it is. Sunshine is my pathway to healing. Too many from my generation are part of the walking wounded. Too many from this generation will soon join us. These are traumatic, fearful times. There are real reasons to be sad and afraid. Leadership can also be about telling the truth and helping the next generation move beyond the pain.

I am wounded. It is what it is. Sunshine is my pathway to healing. Too many from my generation are part of the walking wounded. Too many from this generation will soon join us. These are traumatic, fearful times. There are real reasons to be sad and afraid. Leadership can also be about telling the truth and helping the next generation move beyond the pain.